Rji-pivot-project-reporters-notebook

|

Contents

1. Reporters Notebook

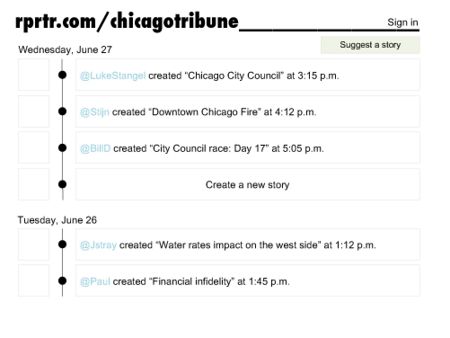

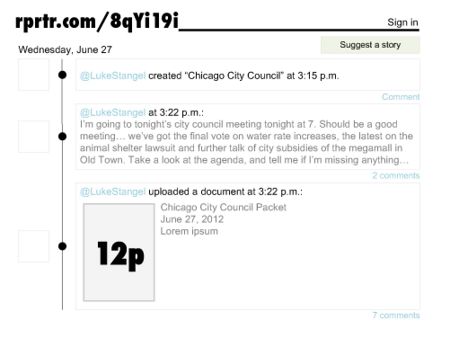

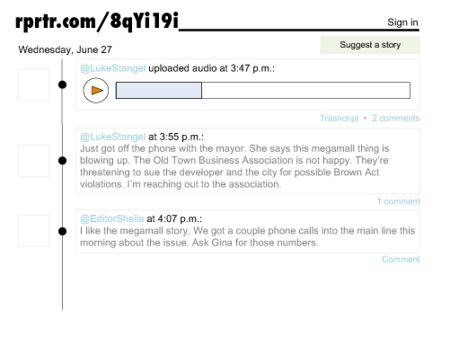

- A method for the public to engage with the reporting process in real time from the moment a story idea is conceived. Reporter's Notebook is Yammer for newsrooms. Reporters create a public page showing each step in the editorial production process, with text, photos, video, documents, links, and transcribed audio. Editors can access the newsroom's live workflow, and comment on the process during the day. The public follows along, commenting on specific content pieces. The resulting goal is total transparency. Champion: Luke Stangel

- BACKGROUND ON LUKE STANGEL

- MORE COMMENTS FROM LUKE ABOUT REPORTERS NOTEBOOK

At a high level, what we're trying to fix here is the public's lack of trust in the journalism process and the reporter's lack of transparency to the public.

If you were to chart out the lifecycle of the average article, it would look something like this:

|---->1---->2---->3---->4---->5---->6-----|

- The reporter decides to write an article about a specific subject.

- The reporter gathers information about the subject alone.

- The reporter writes the article and submits it for editing.

- The editor sees the article for the first time, makes edits, sends it off for publication.

- Article is published. Public sees the article for the first time.

- Public discusses the article, comments on the article and shares the article.

The three interested parties (reporter, editor and the public) have very little visibility with one another. During steps 1-3, the reporter essentially works

alone, gathering and parsing information alone, writing alone. During step 4, the editor sees the article for the first time, and there's (often) very little

time to make significant, structural changes to the work. During steps 5 and 6, the public talks about the article and shares the article, but the reporter and

the editor largely ignore the feedback loop.

By getting the editor and the public involved from step 1, we take a big step toward greater transparency, and collaborative journalism.

Is this too radical for 'journalists'?

Could this product be too radical for journalists? The average reporter is a lone wolf and proud of it. If they use digital tools (like Twitter), they usually do so badly. Journalists are crunched for time, and don't want to adopt something they feel is unnecessary. They don't really want the public and their editors peering over their shoulders watching the work come together. Reporter's Notebook represents a nice sentiment, but it will probably fail completely in the market. Plus, there's no sustainable business model.

That's said, because I believe a product like Reporter's Notebook could be incredibly valuable for journalism. The act of gathering information and crafting it

into an article is a fascinating process, and opening that up to the public would probably generate a lot of interest in that article. Reporters are often seen

as elitist, or inaccessible, so when they make mistakes in their coverage, the public assumes they're either incompetent or biased. By embracing total

transparency, we could build a lot of trust among our readers, viewers and listeners.

What's needed to build Reporter's Notebook

To build something like this, we'd need:

- A developer and a designer.

- Funding to pay for development, design, servers and business development. (I'd estimate $200,000).

- News organizations who would be willing to embrace a radical product like this, getting buy-in from the entire newsroom. Run a 6-month experiment at each

site, and study what works and why.

The first two challenges are relatively easy. The third (IMHO) is astronomically difficult.

I attached a couple of quick PDFs with some wireframe images. Let me know if that works.

A few words about the culture challenge

Luke Stengel adds:

-

Journalists are a funny bunch. They're still largely operating like they did in the 1970s... fiercely independent reporters, all playing out Woodward and Bernstein fantasies of getting The Big Scoop. There's no collaboration with the public... heck, there's very little collaboration inside the newsroom itself.

The San Jose Mercury News has this big moat that circles most of the newsroom: http://bit.ly/PliCYO. I'm sure you've seen it; it's really comical. I'd joke it was to keep the readers out.

Making journalism exclusive is totally a product of our professional culture. The problem is, the world is no longer a linear place... the Internet has fundamentally changed people's expectations of information. They want transparency, honesty and accountability. They want to be able to reach their reporters (you'd be surprised how many newspaper websites still don't list their reporters' email addresses and phone numbers). It's daunting every time I call a newsroom with a tip... and I used to be a reporter. I can only imagine how frightening it is for the average reader.

If I had some extra time and resources, I'd build Reporter's Notebook just to throw it out there as an uncomfortable conversation starter among reporters. I feel like it would challenge us to consider:

(1) Why don't we share a list of the articles we're working on with our competitors?

(2) Why should't the public know what we're working on?

(3) Why shouldn't the public listen to our interviews?

(4) Is the completed article still a valuable unit?

I'd argue that 90 percent of the stuff the average suburban newspaper in a two-paper town produces is not exclusive. It's the supermarket fire, the City Council meeting, the transportation grant the city's getting for restriping the roads downtown, etc. I'd argue if the public got more involved in how the sausage gets made, they'd care more about the final product. Too often, the only readers we know about are the gadflies we ignore. We record 10-minute interviews with well-connected sources, but use one quote and throw the rest away. Why not archive those interviews, and show the public the types of questions we ask the gatekeepers?

Finally, I think the 800-word, completed and edited article as the product is an antiquated way of valuing our work. I think the process is immensely valuable... as is everything that gets left on the cutting room floor.